The Lonely Skepticism of a Bull-Market Skeptic

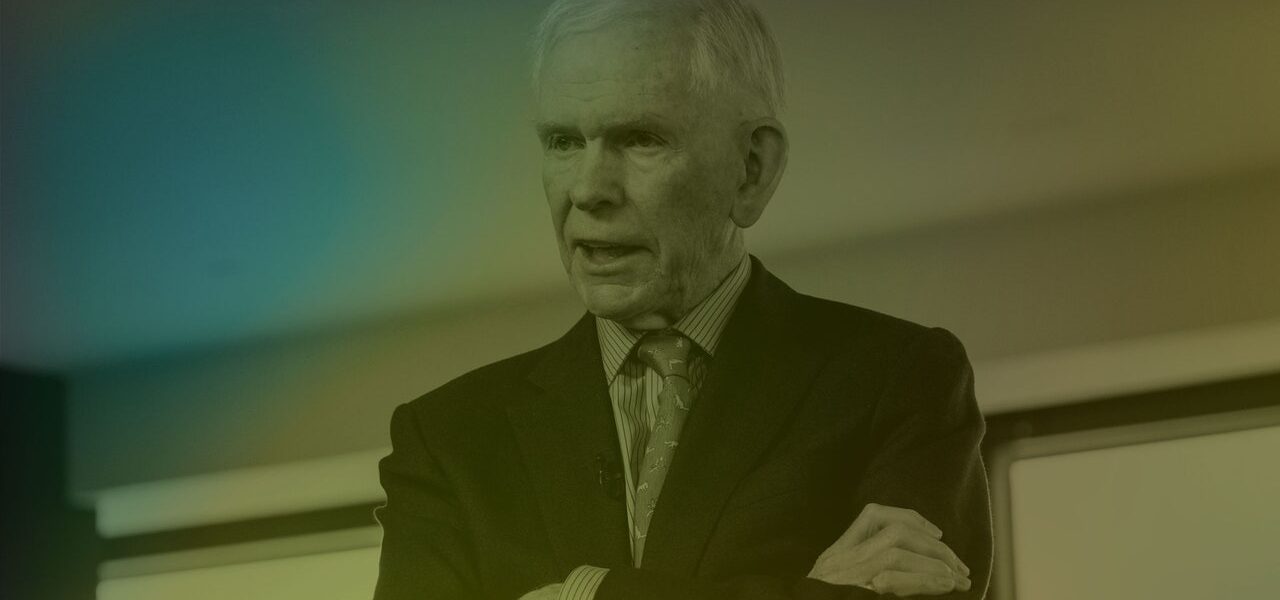

As investor enthusiasm for artificial intelligence, and lately for a Trump Presidency, has been driving the stock market to record highs this year, Jeremy Grantham has been having flashbacks. At the end of the nineteen-nineties, the veteran value investor—one that looks for undervalued stocks—shied away from soaring Internet and technology stocks, believing that their prices had departed from financial reality, and that the market was heading for a crash. Far from thanking him for sounding the alarm, many clients of G.M.O., a Boston-based investment-management firm that Grantham had co-founded, held it responsible for making them miss out on a vertiginous rise in the Nasdaq, which went up by about a hundred and sixty per cent between 1998 and 1999. Some withdrew their money from the company. “We started off in a good position, and in two years we lost almost half of our business,” Grantham recalled. “The clients treated us as if we’d done it deliberately. It was a near-catastrophe.”

Fortunately for Grantham, his skepticism eventually proved well founded. In March, 2000, the dot-com bubble finally burst, and during the subsequent eighteen months the Nasdaq plunged about seventy per cent, inflicting huge losses on those who had got in near the market top. G.M.O.’s investments, which were positioned for the fall, actually made money during this torrid period, and the firm attracted a lot of new clients. “Suddenly, we were superheroes, and the whole thing turned out fine,” Grantham said. “But that was only possible because I was the boss, and I was putting a lot of pressure on people to double down.”

A quarter of a century on, Grantham finds himself in a familiar position as a lonely bear in a market that he regards as a speculative bubble, but which so far has stubbornly defied his predictions of doom. In March of last year, he said that the S. & P. 500 could plunge by fifty per cent: since then, the index has risen by about that much. For this year, despite a tumble last week after the Federal Reserve indicated it will be cautious in cutting interest rates in 2025, the S. & P. 500 is up around twenty-four per cent, and the tech-laden Nasdaq is up nearly thirty-two per cent. Stock in Nvidia, which makes chips that are widely used in large-language A.I. models, has risen roughly a hundred and seventy per cent, and since October, 2022, the month before ChatGPT was released, it’s up tenfold. The firm now has a market capitalization of $3.2 trillion.

Grantham is unchastened. These days, he has retired from day-to-day portfolio management. At G.M.O., he holds the title “long-term investment strategist,” and he is at pains to point out that he doesn’t speak for the firm. But when he called me the other morning from Mexico, where he had just arrived on a vacation, he expressed deep skepticism about an environment that has prompted many of his fellow-bears to recant. In an interview with Bloomberg earlier this month, Nouriel Roubini, an economist whose warnings before the financial crisis of 2008 earned him the nickname “Dr. Doom,” declared, “I would say I am not Dr. Doom: I am Dr. Realist.” Roubini, pointing to the impact of A.I. and other technological innovations, went on: “There are plenty of upsides in economic growth.” Another seasoned skeptic, David Rosenberg, of Rosenberg Research, posted an article on LinkedIn, “Lament of a Bear,” in which he wrote, “I have gained a greater appreciation that it is going to take a whole lot to upset this apple cart.” If there was a modest market correction in the near future, Rosenberg added, his inclination would be to “buy that dip.”

Grantham said that he wasn’t surprised in the least to see some erstwhile bears now making optimistic noises. “The longer the bubble lasts, the more people have to throw in the towel for self-preservation reasons,” he said. “In general, in finance, opposing a bubble is not a survival strategy.” During the dot-com boom, many bearish voices on Wall Street fell silent, and some left their jobs, as their firms sought to profit from the boom by promoting or investing in Internet and tech stocks. In such situations, Grantham said, the competitive pressures and financial incentives to join the crowd can be overpowering. He also cited the real-estate bubble in the years leading up to 2007, when many big banks plunged into the business of cobbling together subprime-mortgage securities, only to get stuck with some of them on their balance sheets when the bubble burst and the securities became practically worthless.

Initially, some of the banks had shied away from subprime, which involves lending to high-risk borrowers, but when they saw their competitors generating hefty profits, they felt obliged to join in. In a famous July, 2007, interview with the Financial Times, Chuck Prince, the chief executive of Citigroup, one of the firms that was subsequently bailed out by taxpayers, said, “As long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance. We’re still dancing.” After reminding me of this quote, Grantham commended Prince, kind of. “He got his timing wrong, but at least he was being honest,” Grantham said.

That’s not to say, of course, that at least some of the analysts and investors who are still recommending (or buying) stock in such tech giants as Nvidia, Microsoft (up nearly a hundred per cent since October, 2022), Google (up more than a hundred and twenty-five per cent), and Meta (up more than five hundred per cent) don’t genuinely believe that A.I. will enable these firms, and others, to make much larger profits in the years ahead. Nvidia, for one, is already benefitting hugely from the boom. This past month, it reported net profits of $19.3 billion for its latest quarter, on revenues of thirty-five billion. On a year-over-year basis, its revenues and profits were both up by more than ninety per cent.

Grantham can’t argue with these figures, obviously, and he doesn’t dispute the assessment that A.I. is a potentially transformative technology. Indeed, he agrees that it is. But he insisted that this doesn’t alter his view that the stock market is in a bubble, a judgment he said was based on his study of history as well as his own experiences. He pointed to elevated market-wide measures of valuation, such as the price-to-earnings ratio, that is the relationship of stock prices relative to corporate earnings. A rise in the P-E ratio indicates that stock prices are growing faster than earnings—a time-tested warning sign for bears like Grantham. Citing the work of his friend Edward Chancellor, a British financial historian, he also noted that the technology-based financial optimism prevalent on Wall Street has been characteristic of many speculative episodes, including the development of canals in England and railroads in the United States. “The more people believe that the technology is utterly transformative, and the more right they are, the more colossal the bubble becomes,” Grantham said. “Because the technology is so important, and is understood to be so important, it sucks in every last single dollar. And of course, A.I., in that sense, is the real McCoy.”

Since November 6th, Trump’s election has only added to the euphoria on Wall Street, where many investors think that tax cuts and deregulation will prove to be another plus for the stock market. Grantham said that he hasn’t yet fully digested Trump’s election, but he regards it as a secondary factor in the market next to the A.I. frenzy, which he dated to the launch of ChatGPT, in November, 2022. During the preceding months, stocks had been falling, following the post-pandemic meme-stock phenomenon in 2021, but they were still highly valued relative to past experience. Grantham said that there is no historical precedent for a new bubble starting when stock prices were already so elevated.

That sounded like yet another risk factor. But Grantham, despite his reputation as an überbear, isn’t predicting an immediate crash. Before he hung up and went to get his breakfast, I asked him about the takeaway from his analysis. “My attitude is ‘Watch your ass,’ ” he replied. “But can it go on for another year, to ruin any value investor who tries to oppose it? Absolutely it can.” ♦